[ SCROLL DOWN FOR ENGLISH VERSION ]

Pavasarį su Arklio Galia lėkėm pasigrot į festivalį “Tallinn Music Week”. Tai vienas iš tokių renginių, į kuriuos specialiai prikviečiama tarptautinių muzikos specialistų, jie rengia diskusijas, skaito paskaitas, pažindinasi su naujom grupėm jų koncertuose ir taip toliau.

Kaip ir galima buvo tikėtis, ekspertų dėmesio našta mūsų nežgriuvo. Užtat užkulisiuose susipažinome su Aston Kais, stebuklinga progroko grupe iš Liepojos.

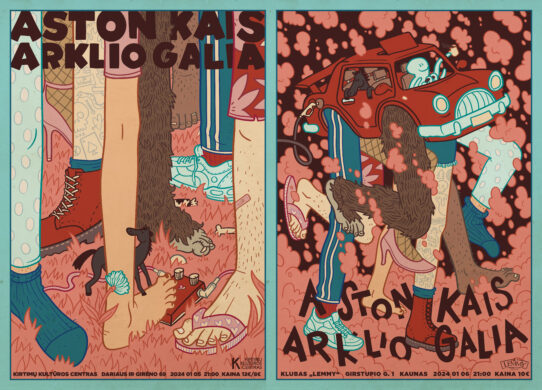

Aston Kais – tarsi vienas didelis besirangantis organizmas iš aštuonių jaunų žmonių, susigrūdusių ant scenos su krūva gitarų. Grojo jie tiesiog super gerai. Iškart nusprendėme vargais negalais juos prisikviesti porai bendrų koncertų Lietuvoje: sausio 5 dieną Kirtimų Kultūros centre Vilniuje, o sausio 6-ąją klube „Lemmy“ Kaune.

Šia linksma proga prisiverčiau pakalbinti Aston Kais narius apie Latviją ir progroką. Kaip dideliam latviškos muzikos mylėtojui, tai buvo itin malonu.

Papasakokite apie dabartinę Latvijos pogrindinės muzikos sceną.

Roberts: Scena tikrai gyva, bet nesu iki galo patenkintas tuo, ką turime. Pastebėjau daug naujų solinių ir elektroninių projektų, atsiradusių covid eros metu, bet muzikos grupių norėtųsi daugiau. Jei tik pasirodo nauja grupė, man iškart labai norisi ją palaikyti. Nauji žmonės visada reikalingi. Daugelis iš mūsų groja dar ir kitose grupėse vien tik dėl to, kad tiesiog yra per mažai muzikantų.

O ar pakanka žmonių, kurie klausytųsi jūsų muzikos?

Roberts: Gal ir nesame iki galo išnaudoję visų resursų, bet turbūt jau dauguma latvių, mėgstančių mūsų grojamą žanrą, žino apie mus. Kitose šalyse dar tikrai yra galimybių – praėjusiais metais grojome Estijoje, Lietuvoje ir Vengrijoje, suradome daug naujų gerbėjų ir ten.

Pačioje Latvijoje dauguma žmonių klauso tik seną kantri muziką arba popsą. Galbūt kai kurie iš jų nueina iki klasikinio roko, bet ne toliau. Mūsų muzika įneša šviežio oro gūsį, tačiau tikrai suprantame, kad tai nėra finansiškai pelningas žanras. Jei ir toliau pavyks užsidirbti pakankamai pinigų naujiems albumams, jau bus šaunu.

Ar jums yra kur pagroti anapus Rygos ir Liepojos?

Roberts: Na, bent jau kol kas tai tik Liepoja ir Ryga. Ar esam groję kažkur kitur, Harijs?

Harijs: Tik festivaliuose.

O pati Liepoja yra vieta, į kurią vis grįžtate kurti muzikos?

Harijs: Taip, tai mūsų namai, čia gyvena mūsų tėvai. Studijavome įvairiose vietose, bet tebesame Liepojos grupė. Šią vasarą savo naująjį albumą irgi įrašinėjome kaime prie Liepojos.

Roberts: Grupės gyvenimas nuo pat pradžių buvo panašus į piligriminę kelionę. Pirmaisiais metais Harijs ir Salvis važinėdavo į Liepoją iš rytinio Latvijos pakraščio. Dabar Liepojoje likom tik aš ir Harijs, o didžioji dalis grupės repeticijų vyksta Rygoje. Tačiau vis tiek Liepoja yra mūsų veiklos epicentras, mums ypatinga vieta. Šis miestas pakankamai mažas, kad jame dar būtų malonu būti, bet kartu ir pakankamai didelis, kad jame būtų šiokio tokio veiksmo.

Pakalbėkim apie jūsų muziką. Prieš penkerius metus pradėjote groti kaip Grupa Harijs ir šiuo pavadinimu išleidote du albumus. Pačios pirmosios jūsų dainos man primena gana tipišką latvišką sentimentalų indie, tokias senesnes grupes kaip Hospitāļu iela ar Baložu pilni pagalmi. Vėliau visiškai pakeitėte muzikinę kryptį ir net grupės pavadinimą. Kaip radote drąsos keistis? Ar nenuvylėte savo gerbėjų?

Harijs: Tai aš nusivyliau – mano vardo nebėra pavadinime… O jei rimtai, tai ko gero, pradėję ir norėjome skambėti taip, kaip skambam dabar, tiesiog neturėjome tam reikalingų įgūdžių ir techninių galimybių. Dabar skambame taip, kaip ir norime.

Ankstyvosios dainos buvo gana paprastos ir lengvai įsimenamos, o naujoji jūsų kūryba yra gerokai sudėtingesnė, ne taip lengvai virškinama. Tarsi galvosūkis, kurį reikia išnarplioti. Tai muzika ne visiems.

Robertsas: Pirmasis albumas buvo labai paprastas. Tai buvo tiesiog pirmieji dalykai, kuriuos pradėjome grojinėti, mums tuo metu buvo 18-19 metų. Aišku, kad tokio amžiaus buvome sentimentalesni ir labiau indie. Dainos buvo pakankamai keistos, kad pritrauktų šiek tiek žmonių į koncertus. Mūsų daina „Montis“ yra tikrai kvaila, tačiau iki šiol tebėra pati populiariausia Spotify. Tuo metu mes patys jau pradėjome klausytis sudėtingesnės muzikos ir pamažu nusprendėme, kad norime groti kažką į tą pusę. Net ir tada, kai dar grojome indie, daug kas iš mūsų klausydavosi visai kitokių dalykų. Aš buvau didelis Tool ir Primus gerbėjas, Jonatanas likusiems grupės nariams pristatė King Gizzard & the Lizard Wizard, mes juos iškart pamilome. Pradėjome greitai augti.

Harijs: Šią vasarą festivalyje “Kartupeļpalma” švęsdami Grupa Harijs penktąsias metines po ilgo laiko sugrojome dainą „Montis“, tik perdarę ją į triukšmingą drum’n’bass/punk.

Mano įsitikinimu, iki King Gizzard’ams pradedant leisti progresyvesnius albumus, progrokas buvo senų hipių ir nišinių melomanų dalykas. Vėliau ir daugiau jaunų grupių atgaivino šį žanrą. Šiuo metu jis jau tikrai visai populiarus tarp hipsterių visame pasaulyje. Laikote save šiuolaikinio progroko mėgėjais ar labiau prijaučiat klasikai?

Harijs: Manau, modernaus progroko klausausi daugiau nei senojo. Nenorime būti senamadiški, tiesiog stengiamės kurti gerą roką. Norint skambėti labiau oldskūliškai, reiktų žinoti, kaip tai daryti, praktikuotis ta linkme. Mes tikrai nesistengiame skambėti senoviškiau.

Robertsas: Mano ankstyvieji favoritai buvo Porcupine Tree ir Tool, vėliau atsirado King Gizzard. Tik visai neseniai pradėjome atrasti senesnius kurėjus. Jonatanui labai patinka Emerson, Lake & Palmer, Mahavishnu Orchestra. Tai itin sudėtinga muzika ir turbūt traukia Jonataną kaip džiazo muzikantą. Aš irgi pastaruoju metu atradau keletą puikių atlikėjų, pavyzdžiui, Ambrosia. Netgi Supertramp ’70-aisiais grojo šį bei tą į progroko pusę. Kuo vyresni tampame, tuo dažniau norisi atsigręžti į praeitį ir ten ieškoti idėjų ir dalykų, kuriuos galėtume pabandyti.

Ar manot, kad progrokas yra protestas prieš paprastą ir nuspėjamą muziką?

Roberts: Kūryboje stengiuosi būti labai atsargus. Groti progroką vien tik dėl sudėtingumo yra gana pašlemėkiška. Kai nori visiems pasirodyti, kad moki groti iš septynių ar trylikos, nepaisant to, kad pati muzika skamba šūdinai. Pavydžiui, grupė Broken Social Scene turi dainą „7/4 (Shoreline)“, ji yra 7/4 metre, bet viskas ten skamba labai natūraliai, keistas metras labai papildo dainą. Ji tiesiog būtų gerokai mažiau įdomi, jei būtų grojama įprastame 4/4 metre. Net ir į pop dainas įdėti šiek tiek sofistikacijos yra labai faina. Žinoma, egzistuoja nuomonė, kad progrokas privalo būti labai sudėtingas, bet man visada svarbiau, kad daina būtų gera.

Aš asmeniškai manau, kad muziką, pristumiančią prie muzikinių gebėjimų ribos, tiesiog daug smagiau groti. Ar sutinkate?

Harijs: Prieš kelias dienas kalbėjausi su Jonatanu, mūsų gitaristu, apie tai, kodėl mums patinka sudėtinga muzika. Mano nuomone, tai – tarsi žaidimas. Negali žaisti futbolo rankomis, nes tai būtų per daug paprasta, todėl žaidi kojomis. Mes sugalvojame vis sudėtingesnes dainas tam, kad būtų vis smagiau, kad mūsų žaidžiamas žaidimas taptų dar įdomesnis.

Jūsų muzikoje nemažai linksmumo, energijos ir azarto, kai tuo tarpu didžioji dalis progresyvaus roko albumų yra rimti, pretenzingi ir monumentalūs.

Harijs: Taip tikrai galėsi sakyt apie kitą mūsų albumą.

Roberts: Taip, kitas albumas bus šiek tiek rimtesnis. Kadangi pati muzika sudėtinga, savaime norisi, kad ir albumai būtų labai sudėtingi ir gilūs. Dėl to, bene kiekvienas progroko albumas yra apie pasaulio pabaigą ar kažką panašaus. Reikia būti gana atsargiam, kad vėl ir vėl nenuklystum tuo pačiu keliu. Turėjom keletą situacijų, kai sakėm “joo, nedarykim taip, tai siaubinga”. Gerai, kad turime net aštuonis grupės narius, todėl mūsų savimonės lygis sąlyginai aukštas. Mūsų muzika pereina daug filtrų, kol išvysta dienos šviesą.

Kai grupėje tiek daug žmonių, kaip dalijatės įkvėpimu? Ar dažnai visiems patinka tie patys dalykai?

Harijs: Visi klausomės gana skirtingos muzikos. Vienintelis dalykas, kurio klausomės visi, yra King Gizzard & the Lizard Wizard. Galbūt dar latvių grupės, tokios kaip JUUK ar Hospitāļu iela. Trys iš mūsų studijuoja džiazą ir daugiausia klausosi džiazo. Kiekvienas narys tiesiog klausosi to, kas jam pačiam patinka.

Ar įmanoma aštuoniems žmonėms kartu parašyti dainą?

Roberts: Nemanau. Trys žmonės turbūt yra daugiausia, kiek įmanoma įtraukti į muzikos sukūrimą. Tekstą kurti geriausia vienam arba dviese.

Harijs: Kai jau yra kažkokia pagrindinė idėja, mes visi kartu aranžuojame. Jei kiekvienas iš aštuonių narių pasiskirstytų pareigomis, pavyzdžiui vienas žmogus atsakingas už žodžius, kitas už harmoniją, trečias už ritmą ir t. t., būtų visai įdomus kūrybinis žaidimas, bet vargu, ar tai būtų produktyvu.

Taline, kur susipažinome, kalbėjausi su senu ilgaplaukiu iš Suomijos. Jis buvo visiškai susižavėjęs jūsų muzika, jam priminėte Rush ir Jethro Tull. Esu tikras, kad turite ir galybę labai jaunų gerbėjų. Ką manote apie amžių ir muziką? Kodėl skirtingo amžiaus žmonės klauso skirtingos muzikos?

Harijs: Manau, kad pagrindinė mūsų auditorija yra jaunimas. Prieš kelerius metus tai daugiausia buvo 15-18 metų paaugliai. Jiems buvo įdomu, kad mes, būdami tik vos vos vyresni už juos, jau kuriam savo muziką ir apskritai kažką darom Liepojoje.

Roberts: Nuo tada, kai tapome Aston Kais, tai pasikeitė. Dabar dauguma mūsų klausytojų yra tarp 30 ir 35 metų. Ir daug daugiau bičų. Anksčiau buvo net apie 70 proc. merginų, Spotify pateikia visus šituos duomenis. Rygoje ar Liepojoje esame sutikę kelis vyresnius žmones iš senosios progroko kartos, kurie mums sakė “oo, chebra, jūs man primenat senus gerus laikus”. Gera turėti ir tokių klausytojų.

Šiaip, jaunimas nėra labai linkęs domėtis senesne muzika, o vyresni žmonės – nauja. Net kai kalbama apie kone tą patį žanrą. Pavyzdžiui, neseniai supratau, kad Lietuvoje dauguma senų rokerių beveik nieko nežino apie naujas roko grupes. Kaip supažindinti juos su nauja muzika?

Roberts: Gerai, jei pavyksta maloniai nustebinti vyresnio amžiaus žmogų, bet šiaip dauguma nėra labai lankstūs. Kuo vyresnis pats tampu, tuo labiau suprantu, kad jei kažkas man dabar patinka, tai turbūt visada ir patiks. Šiaip, mes patys turbūt neužsiimam tokia sklaida. Harijs, ar turi kokių nors idėjų?

Harijsas: Kai pradėjome muzikuoti, juokavau, kad, jei mano mamai nepatiks, vadinasi, viskas gerai, mes viską darom teisingai.

Dauguma žmonių klausosi muzikos, atliekamos jiems suprantama kalba. Kaip jaučiatės dainuodami žmogui, kuris nesupranta nė žodžio? Ar neatrodo, kad taip iš kūrinio atimama didelė dalis turinio?

Harijs: Nesu tikras, ar patys latviai supranta mūsų dainų tekstus. Pirma, tuos tekstus ir šiaip sunku suprasti, o antra, gyvo garso koncerte tikrai sunku klausytis žodžių. Nebėda net jei ir nesupranta. Stengiamės kad mūsų dainų žodžiai turėtų prasmę, žinutę, tai būtų tam tikra malda. Tokiu būdu net jei klausytojas nesupranta konkrečių žodžių, jis gali pajusti dainų žodžių dvasią iš žmogaus, kuris dainuoja.

Ar gali keliais žodžiais papasakoti, apie ką daugiausia yra jūsų dainos?

Harijs: Paskutinis albumas yra apie magiškus personažus. Kiekvienas personažas turi vieną problemą – jie bando gyventi su mirtimi. Tekstai yra apie tai, kaip jie tvarkosi su mirtimi.

Daugelis grupių tarp dainų paaiškina savo dainų tekstus, ant albumų viršelių deda angliškus vertimus. Kartą nuėjau į latvių grupės Ansamblis Manta pasirodymą Vilniuje, kur televizoriuose buvo gyvai transliuojami angliški subtitrai. Kai kurie atlikėjai netgi kuria tų pačių dainų versijas skirtingomis kalbomis. Atrodo, jiems itin svarbu būti iki galo suprastiems. Ar kada nors svarstėte apie ką nors panašaus?

Harijas: Galbūt paaiškinti, bet ne versti.

Robertsas: Manau, geriau leisti muzikai kalbėti pačiai už save. Viena mano mėgstamiausių grupių Sigur Rós dainuoja islandiškai arba savo pačių sugalvota kalba. Jų muzika tokia gera, kad man jos klausantis niekada neprireikė vertimų. Kai kažkada vėliau susigūglinau apie ką jų dainos, dar labiau įsimylėjau šią grupę.

Pažįstu vos kelis lietuvius, kurie klausosi latviškos muzikos įrašų. Ar patys klausotės daug tarptautinės, ne anglakalbės muzikos?

Roberts: Kai nuvykome groti į Budapeštą, radau seną Logomotiv GT vinilinę plokštelę, tikrai šauni 70-ųjų grupė iš Vengrijos. O vasarą užsikabinau už Anatolijos roko ir graikų muzikos. Patys stengiamės kuo daugiau dalytis muzika tarpusavyje, plėsti akiratį.

Prieš pradėdamas domėtis latvių muzika, maniau, kad kiekvienas žymesnis Lietuvos atlikėjas turėtų turėti latvišką atitikmenį, nes mūsų šalys tikrai daug kuo panašios. Visgi vėliau pamačiau, kad yra nemažai reikšmingų skirtumų. Pavyzdžiui, latviai devintajame dešimtmetyje turėjo daug puikaus new wave, kai tuo tarpu Lietuvoje jo beveik nebuvo. O su free džiazu yra atvirkščiai – lietuviai tiesiog dievina free džiazą, ypač Vilniuje.

Harijs: Tikras stebuklas, kad Lietuvoje yra tiek daug free džiazo. Gal čia kaip sporte? Jei tavo ledo ritulio komanda laimi čempionatą, visi vaikai nori lankyti ledo ritulio treniruotes. Jei šalis turi tokį puikų free džiazo saksofonininką kaip Liudas Mockūnas, visas jaunimas nori groti kaip Liudas. Aišku, tai gali būti ir specifinis šalies mentalitetas. Mūsų mentalitetai skirtingi, istorijos skirtingos. Estijos istorija taip pat skirtinga. Gal todėl ir muzikinis skonis yra šiek tiek skiriasi.

Kaip priversti latvius klausytis daugiau lietuviškos muzikos? Lietuvoje visaip bandau populiarinti latvių muziką, dažnai mano draugai net šaiposi iš manęs dėl šito. Bet kai kuriems iš jų visai patiko Aston Kais, DZ ar Nikto.

Roberts: Kai man buvo maždaug 16 metų, Liepojoje grojo Garbanotas. Gal ne pati išskirtiniausia muzika, bet šiek tiek kitokia nei tai, ką buvau matęs iki tol. Retkarčiais vis dar jų pasiklausau, jie tikrai neblogi. Jei muzika gera, aš jos klausausi, nesvarbu, iš kur ji būtų.

Harijs: Tai, ką planuojame daryti sausį, yra visai geri mainai. Atvyksime į Lietuvą pagroti su Arklio Galia ir žmonės, kurie žino jus, bet nepažįsta mūsų, ateis į mūsų bendrą koncertą. O vėliau darysime atvirkščią dalyką Rygoje ir Liepojoje. Taip pat turėtumėte pabandyt pagroti mūsų festivaliuose.

King Gizzard gyvena Melburne, Australijoje, bet yra gerokai populiaresni JAV. Ar nemanot, kad galbūt ir jūsų potenciali publika gyvena visai kitoje šalyje? Galbūt jums reikia vykti į Albaniją ir būti žvaigždėmis ten?

Roberts: Kaip jau sakiau, Latvijos rinkoje turbūt jau susiradome didžiąją dalį savo klausytojų. Kai kuriose kitose šalyse progrokas mylimas labiau. Galbūt arčiau Vokietijos ar Britų salų. Aišku, Jungtinės Amerikos Valstijos šiuo metu yra šio žanro namai ir Gizzard’ai tarsi atrado save ten. Galbūt ir mes kažkur sulauksime sėkmės.

Ar labiau esate grupė, turinti svajonių, tikslų ir rimtų planų, ar tiesiog gyvenate šia akimirka ir improvizuojate?

Harijs: Taip, turime rimtų planų atvykti į Lietuvą!

Roberts: Tikrai norime nuveikti didelių dalykų. Kol kas tai puikus hobis, albumų įrašai atsiperka ir esam gan komfortiškoje padėtyje. Kitas žingsnis gali būti šiek tiek sunkesnis, bet manau, kad būtent ten ir norim eiti.

Ačiū!

Aston Kais ir Arklio Galia sausio 5 d. gros Kirtimų Kultūros Centre Vilniuje, o sausio 6 d. – “Lemmy” klube Kaune.

[ ENGLISH VERSION ]

Last spring we drove to Tallinn Music Week to do a gig with my band Arklio Galia. It is one of those events which have a lot of international music professionals coming, they participate in panel discussions, do presentations, go to shows of new, lesser known bands and so on.

Of course, the attention of experts did not fall upon us, but in the backstage we got acquainted with Aston Kais, a wondrous prog rock band from Liepāja.

Aston Kais seemed like a big wobbly organism made up from eight young people, completely filling up the stage with their many instruments. And they played super well! We instantly decided to invite them to Lithuania to do a couple of gigs together. These plans finally came into action – Aston Kais and Arklio Galia will play Kirtimų kultūros centras in Vilnius on January 5th and “Lemmy” Club in Kaunas on January 6th.

On this joyful occasion I brought myself to do an interview with two of Aston Kais, to talk a bit about Latvia and prog rock. It was very pleasant for me as I’m a big lover of Latvian music.

Please tell me a few words about the current underground music scene in Latvia.

Roberts: It’s alive, but I’m not quite satisfied with what we have here. I’ve seen a lot more solo and electronic projects coming out of the covid era, but in terms of bands, I’d like some more. Whenever there’s a new band, I’m already their supporter. There is always a need for new bands to fill out the scene. A lot of us play in other bands, just because there’s not enough folk.

Are there enough people to listen to your music?

Roberts: I don’t think that we’ve exhausted all the resources, but pretty much all the people in our country who like this genre already know of us. In other countries there’s still opportunity. Last year we played in Estonia, Lithuania and Hungary, we started to get lots of fans from those places too.

In Latvia, there are people who enjoy old school country music and a generation younger people who enjoy regular pop. Maybe some of them will go as far as classic rock. We’re offering a breath of fresh air, but we’ve always understood that it won’t be a money making genre. If this results in us being able to make enough money for new albums, it’s a cool thing.

Is it just Riga and Liepāja or can you go to a smaller city and play there?

Roberts: At least for now, it’s Liepāja and Riga. Have we played anywhere else, Harijs?

Harijs: In festivals only.

Is Liepāja the place where you come back to create music?

Harijs: Yes, it is our home, our parents live here. We studied in many places, but we’re still based in Liepāja. This summer we recorded our new album in the countryside near Liepāja.

Roberts: It has always been a pilgrimage. At the very beginning Harijs and Salvis used to come to Liepāja from the far eastern end of Latvia. Now only me and Harijs are in Liepāja and most of the band practice is in Riga, but Liepāja is the heart and core of the whole operation. There’s something about Liepāja that makes it special. It’s small enough to be enjoyable and also big enough for things to happen there.

Let’s talk about your music. Five years ago you started out as Grupa Harijs and had two albums under that name. First songs were not far from what I consider typical sentimental latvian indie, bands like Hospitāļu iela or Baložu pilni pagalmi. Later, you changed the musical direction and even the name of the band. Where did you find the courage to change? Did you disappoint your fans?

Harijs: It’s disappointing for me – it’s not my name anymore… I think when we started we wanted to sound like we sound now but our possibilities and skills weren’t so good. Now we sound like we want.

Those early songs were simple and easy to sing along, but your new music is much more difficult and not so easily digestible, like a puzzle that needs to be untangled. It’s not for everyone.

Roberts: The first album was very simplistic, it was just the first things that we started playing, most of us were 18 or 19. Of course we were more sentimental and more indie. We started playing some concerts and the songs were quirky enough to get some people. For example, “Montis” is a really stupid song and at the same time it still remains the most popular in Spotify. But at that time we started to listen to more sophisticated music ourselves and out of that slowly we decided that it is what we want. Even when we played indie, lots of us listened to some other stuff. I was a big fan of Tool and Primus, Jonatans presented King Gizzard & the Lizard Wizard to the rest of the band and we fell in love with them. We started to grow up fast.

Harijs: this summer we celebrated Grupa Harijs 5th anniversary in Kartupeļpalma festival and we played “Montis”, but in a very loud drum’n’bass/punk way.

In my opinion, up until King Gizzard made their first prog sounding albums, most of the progressive rock used to be a thing for old hippie dads and niche music lovers. Later there were quite a lot of new bands who revived this genre and now hipsters listen to new prog rock all over the world. Do you consider yourselves modern prog rockers or are you lovers of the old stuff?

Harijs: I guess I listen to more modern prog rock, we don’t try to be old-school, we just try to make good rock. To sound more old-school, you need to know how to do it, to really practice it. We are not trying to sound more old-school.

Roberts: I think at the beginning we did some more new-school, Porcupine Tree and Tool were my early favorites and then King Gizzard came along. Now recently we started to discover a lot more of the old-school. Jonatans really likes Emerson, Lake & Palmer, the Mahavishnu Orchestra. That’s some complicated stuff, I think he likes that because he’s more kind of a jazz player. I’ve discovered some great ones too, like Ambrosia. Supertramp even have proggy albums if you take it back to the 70s. As we are growing older, we are looking back to the old-school to look for some ideas and things that we can do.

Do you think that prog rock is a protest against simple and predictable music?

Roberts: I’m still very careful when it comes to writing our own songs. Prog rock for the sake of sounding sophisticated is kind of a douchebag move. When you’re showing off that you can play in 7 or 13 even if it sounds like shit. The band Broken Social Scene has a song called 7/4 (shoreline) which is in 7/4, but it feels very natural, it adds to the song. If it was in 8 or in 4, it wouldn’t be so interesting. Even if pop songs have a little bit of sophistication, I find it kinda cool. There’s an opinion that prog rock has to be super complicated. I always like it when a song is good and it has prog rock elements to it, making it all work together.

I think that music which pushes you to the edge of your musical ability is simply fun to play. What do you think about it?

Harijs: I was speaking some days ago with Jonatans, our guitar player, about why we love complicated music. My opinion is that it’s like a game. You can’t play football with your hands, it would be too easy, you play it with your legs. We think of more and more complicated songs to make it more fun, a more interesting game to play.

In my opinion, your music is more about fun, energy and excitement, while most of the world’s progressive rock is trying to be serious, pretentious and monumental.

Harijs: You will say these things about our next album.

Roberts: Ha ha, well the next album will be a little bit more serious. You know, the music of prog rock is already complicated, so you want to make the albums very complicated and deep too. And so, every album is about the end of the world or something like that. You have to be very careful not to go down that route again and again. We had some situations where we’re like “yeah, let’s not do this, it’s horrible”. It’s really good that we have eight band members, because it’s a certain level of self-awareness. The music passes through a lot of filters before it sees the light of day.

With so many people in the band, how do you share inspirations? Is it often that you all like the same thing?

Harijs: We all listen to quite different music. The only things that all of us listen to is King Gizzard & the Lizard Wizard and maybe Latvian bands like JUUK or Hospitāļu iela. Three of us study jazz and listen mostly to jazz, other members listen to things that they like.

Is it possible for eight people to write a song together?

Roberts: No, three is probably the most you can involve to write the music, one or two write the lyrics.

Harijs: After there already is the big idea, we arrange together, that’s how it works. If each of the eight members had a particular duty – one person for the lyrics, another for harmony, another for rhythm, and so on, it would be an interesting game, but it wouldn’t be productive.

In Tallinn, where we met, I talked to an old long-haired Finnish man, who was totally fascinated with your music because you remind him of Rush and Jethro Tull. I’m sure you have a lot of very young fans as well. What do you think about age and music? Should there be different music for different aged people?

Harijs: I guess our main audience is youth. Few years ago it was mostly 15-18 year old teenagers. It was interesting for them that some guys, just a bit older than they are, play music and do some action in Liepāja.

Roberts: Since we became Aston Kais, it changed. Now it’s mostly 30-35 year olds. And a lot more dudes. Before it was 70% girls, Spotify gives you all the data. In Riga or Liepāja we have met one or two older guys from the last prog generation and they’re like “whoa man you remind us of those good times”. It’s good to have those people too.

Recently I realised that young people don’t want to listen to old music and older people are even more sceptical about new music, even if it’s almost the same genre. In Lithuania, a lot of the old rockers know nothing about the new bands. How would you introduce new music to them?

Roberts: In my experience – if you can surprise older people in a pleasant way, it’s good, but they’re more rigid. The older I become, the more I understand that if there’s something that I like, it is most likely going to stay the same. We don’t focus too much on that outreach ourselves. Harijs, do you have any ideas?

Harijs: When we started playing music, I had a joke: If my mother doesn’t like it, then everything is fine, we do it the right way.

Most people listen to music which is in a language that they can understand. How do you feel singing to somebody who doesn’t understand a word of the lyrics? Do you feel that a big portion of your creation is being taken away from you?

Harijs: I’m not sure if even Latvian people understand it. Firstly, it’s not easy to understand our lyrics at all, and it’s even more complicated to hear what we sing in a live concert. For me it’s not a big problem if people don’t understand. I try to put some meaning, manifest and prayer in the lyrics and even if the people don’t understand the words, they can feel the power and spirit of the lyrics from the singer.

Could you tell, in a few words, what your songs are mostly about?

Harijs: The last album is about magical characters. Every character has one problem – they try to live with death. It’s about how they deal with death.

Many bands explain their lyrics between songs, put English translations on album covers. I once went to Latvian band’s Ansamblis Manta show in Vilnius where they had TV screens with subtitles which were in sync with live music. Some artists even make different language versions of the same songs. It’s so important for them to be understood completely. Did you ever consider something like that?

Harijs: Maybe explaining, but not translating.

Roberts: I think it’s better to let the music speak for itself. One of my favorite bands, Sigur Rós sing in Icelandic or a language that they made up themselves. The music’s so good that I never needed translations while listening to it. I googled the meanings afterwards and it made me fall in love with the band even more.

I know just a few Lithuanian people who listen to Latvian music records. Do you listen to a lot of international, non-english music yourselves?

Roberts: When we went to Budapest, I found an old vinyl of Logomotiv GT, a really cool 70s band from Hungary. This summer I fell into Anatolian Rock and Greek music. We try to share as much as we can amongst ourselves. We try to broaden the horizons.

Before I started to look into Latvian music, I thought that there should be a Latvian counterpart for every famous Lithuanian artist, because our countries are so similar in a lot of ways. Later I saw that there are quite a lot of differences. For example, Latvia has a lot of very nice new wave from the 80s, while Lithuania has almost none. With free jazz it’s the other way around. Lithuanians just love free jazz, especially in Vilnius.

Harijs: It’s a miracle that there’s so much free jazz in Lithuania. Maybe it’s like in sports? If your hockey team wins a championship, all the kids want to go to hockey training. If you have a great free jazz saxophone player like Liudas Mockūnas, all the youth wants to play like Liudas. It could also be a specific mentality. Our mentalities are different, histories are different. History of Estonia is also different. Maybe that’s why the musical taste is different.

How to make Latvians listen to more Lithuanian music? I try to promote Latvian music as much as I can, my friends are even making fun of me for that! But some of them really liked Aston Kais, DZ and Nikto.

Roberts: When I was 16 or something, we had Garbanotas in Liepāja. Not the most sophisticated music, but a little bit different than what I had seen so far. I still listen to them from time to time. It’s good. If it’s good music, I will listen to it, no matter where they are from.

Harijs: What we’re gonna do in January could be a good plan for exchange. We’ll come to Lithuania to play with Arklio Galia and people who know you, but don’t know us will come to our show. Later we’ll do the opposite thing in Riga and Liepāja. And you also should come to the festivals.

King Gizzard live in Melbourne, Australia but are much more popular in the USA. Do you think that maybe your potential fans live somewhere else too? Maybe you need to go to Albania and be stars there?

Roberts: As I said, we probably found most of our fans in the Latvian market already. There’s definitely more fans of prog rock somewhere else. Maybe closer to Germany or the British Isles. The United States now is the home of the genre and I think Gizzard kinda found themselves there. Depending on how we go, we might get some success too.

Are you a band that has dreams, goals and serious plans or do you just live in the moment and improvise?

Harijs: Yes, serious plans to go to Lithuania!

Roberts: We definitely want to do big things. For now it is a great hobby, albums pay for themselves, we are at a comfortable position. The next step might be a little hard to get, but I think that’s where we want to go.

Thank you!

Aston Kais and Arklio Galia are playing in Kirtimų Kultūros Centras in Vilnius on January 5th and Lemmy Club, Kaunas on January 6th.

Komentarai